In February of this year I joined the IMR team as a PADI Divemaster candidate and a Research Assistant in training. I expected to learn a ton about protocol and methodology for conducting marine research surveys, fine tune my dive skills, and contribute to the Institute for Marine Research’s goal of monitoring and protecting Dauin’s coral reefs. I did not, however, expect to observe a crown-of-thorns outbreak and be an integral part of the team who stepped in to manage it. It was a unique experience, and seeing the process from beginning to end provided me with significant insight on the level of concern and the integral work institutions like IMR perform.

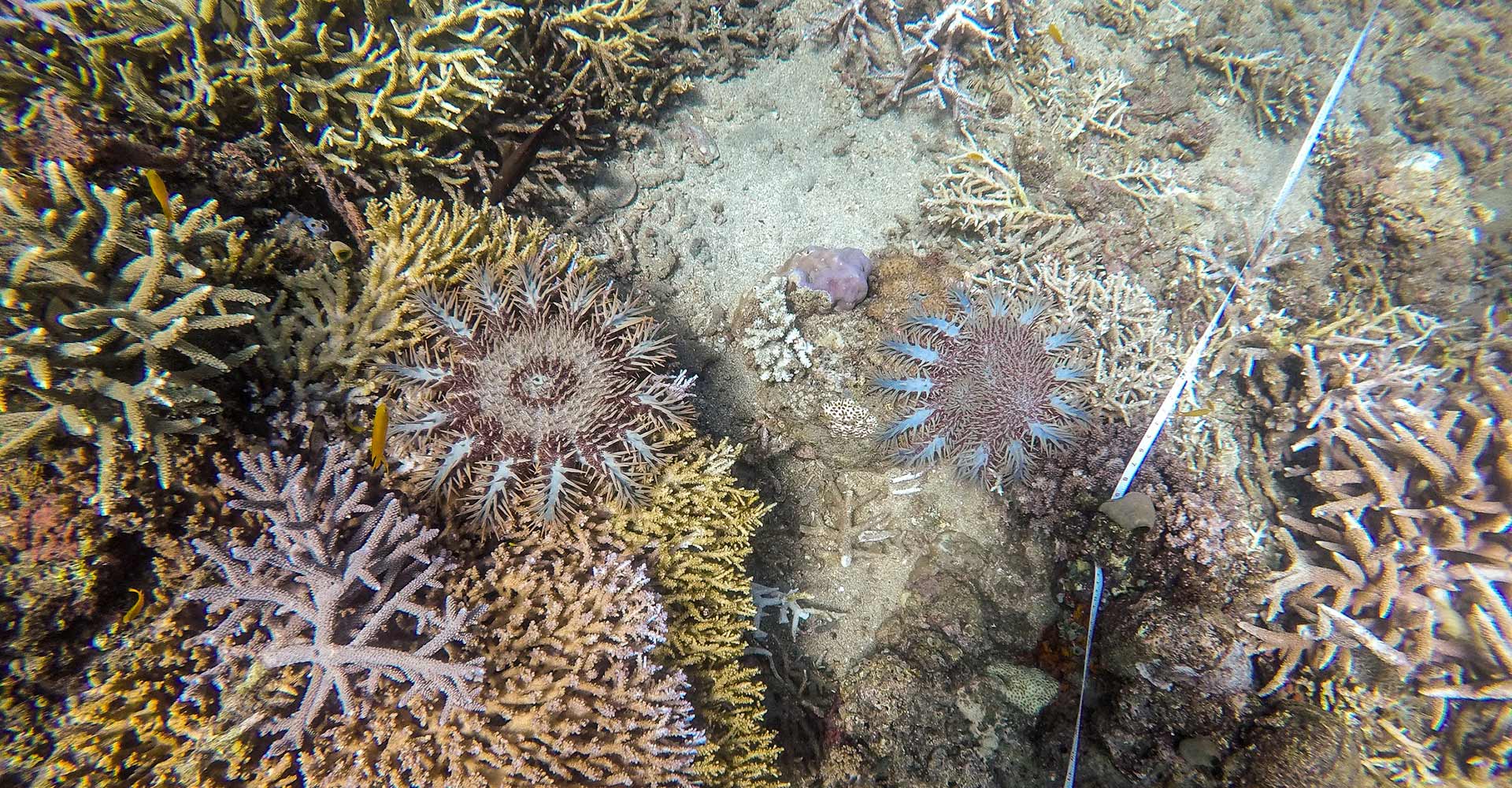

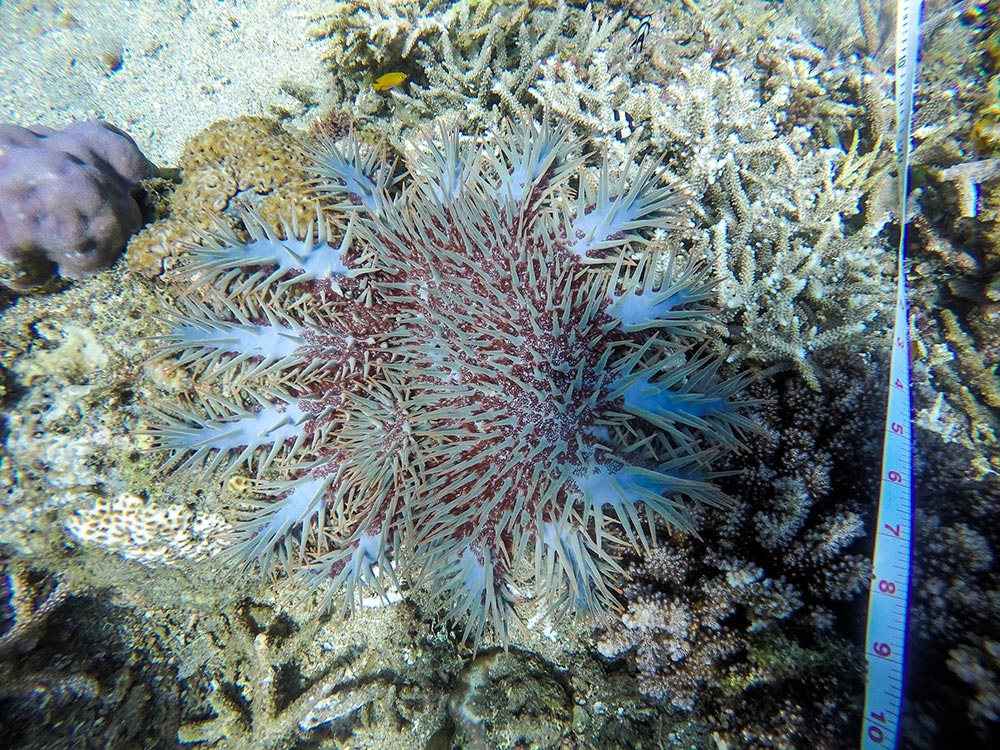

Crown-of-thorns starfish (COTS), or Acanthaster plancii, is a relatively well known coral predator who, in small numbers, helps to maintain the coral diversity of the reef. However, when outbreaks occur, they can severely damage the health of the reef by overtaking and rapidly destroying the corals that the reef system and the creatures within it rely on. For this reason, when we started noticing an increasing number of COTS and COTS feeding scars along IMRs usual 50 meter transect, it grabbed our attention. It was determined further inspection was necessary to determine if this reef was in the middle of a COTS outbreak.

According to IMR protocol, dive teams were created to go out and inspect the situation further, gather information on COTS present, their size, what depth they were found, presence of any feeding scars, on what coral genera they were feeding, the size of scars present and size of coral colony affected. During these dives we noticed a greater prevalence at shallower depths, even as shallow as 1 meter. Therefore, additional snorkel COTS surveys were conducted to explore these shallower depths and gain a better perspective of the number of COTS present there. Max depth surveyed was 6 meters as numbers dramatically tapered off at deeper depths. After analysis of the collected data it was determined that numbers in this region were much higher than normal and an outbreak was occurring, as a result IMR determined the best plan of action would be to conduct a cull.

The collected data was summarised and taken by Chelsea (IMR Creator and Director), accompanied by Ella (IMR Masters student), to the Dauin Coastal Resource Manager, Arlene, with the goal of expressing that a cull was advised by the research team. Analysis of the presented data and accompanying discussion concluded that the number of COTS was alarming, and steps needed to be taken to manage the numbers present. Arlene then took this matter to the Dauin Fishermen’s Associations, who oversee all of Dauin’s Marine Protected Areass, for permission to begin culling measures. After the Fishermen’s Associations were on board, Chelsea and Arlene consulted with the mayor of Dauin, Galic Truita, for final approval. This entire process took a total of just 4 days, and then culling measures were set to begin.

IMR prepared it’s culling teams by providing a lecture in advance; outlining the anatomy of the crown-of-thorns starfish highlighting their water vascular system, which is key to the culling procedure. Specifically the space between leg and central disc where these creatures need to be injected with household white vinegar for a cull to be successful, so this area was stressed to those involved in culling procedure. Cull protocol required gloves to be worn by team members. 60 ml capped syringes are filled with vinegar for COTS injections (each can target 3 individual starfish), teams were comprised of two; one individual recording (COTS present, size, injected/not able to reach, any scars present in immediate area) and one injecting (each COTS with 20 ml of vinegar).

Two days post cull, a follow up survey dive was conducted to determine the effectiveness of the first round of injections. Expired COTS were observed and had clearly been predated on: the cull was a success. After confirming our technique was effective, the IMR team went out and did another cull to try to inject those individuals we were unable to target on the first round.

Out of concern for neighbouring reef health, any site previously surveyed where impacts data recorded COTS scars were observed, IMR conducted COTS survey dives on. Results of these dives indicated population numbers were in check at the neighbouring reefs, and it was confirmed to be a site specific outbreak; impacting only the Marine Protected Area Masaplod Sur.

At this point IMR is still looking into reasons why this COTS outbreak may have occurred, in order to advise/take action to prevent future outbreaks. Some ideas as to what may have contributed is that the coastline around Masaplod Sur is highly developed, and as a result lacks vegetation. This breakout occurred at the end of Dauin’s wet season. Without sufficient vegetation, the reef is not as protected from run-off entering the water which could result in an influx of nutrients into the reef system. COTS thrive in nutrient-rich water, and Masaplod Sur is dominated by Acropora fields, a fast growing coral which is favoured as a food source by COTS. These factors combined may have created ideal conditions for an outbreak to occur. At this point this is just speculation, and further investigation is necessary to have a complete understanding.

Unfortunately, further exploration into causality and the long term impacts of tackling this COTS outbreak have been temporarily and involuntarily placed on hold, with the onset of the COVID-19 crisis. As a result, the IMR research team has not been able to get back into the water to monitor things further, as would be standard protocol. So although initial efforts to control COTS numbers in this region were a success, the current state of this outbreak is unknown. When IMR is able to resume normal practice and get back out into the water, this matter will be followed up on and monitoring is planned to continue.

Having the opportunity to be a part of this effort was a fulfilling and incredibly interesting experience. I wanted to volunteer with IMR because I have a great passion for conserving our coral reefs, and I wanted to come and contribute to the great work IMR is doing with their long term reef monitoring project. I didn’t expect my efforts with IMR to be apparent immediately, but that they would contribute to the long term health of the Dauin reefs. Being able to participate in this COTS cull allowed me to see the almost immediate results of our efforts, which was truly rewarding.